Thomas Wright published "The Romance of the Lace Pillow" in 1919. The subtitle is "The History of Lacemaking in Bucks Beds, Northants and neighbouring counties, together with some account of the lace industries of Ireland and Devon". It was published by H.H.Armstrong, in Olney, Bucks. See online lace books for the complete book.

This is taken from the chapter on lace tells, the songs that lacemakers sung as they did their work.

The proficiency of the children at the Lace Schools was, as we have already noticed, estimated by the number of pins placed in an hour, and to assist themselves in the counting they used to chant in a sing-song voice the amount of work to be got over:

|

20 miles have I to go, 19 miles have I to go, 18 miles have I to go. |

These and the more elaborate countings were called Lace Tells.

...

The simplest of the tells took the bald Dialogue form:

|

Knock, knock at your door. Who's there? It's me. Come in. Does your dog bite? Yes. How many teeth has it? Six; seven next time; eight when I call again. |

Silence was then kept while eight pins were stuck into the pillow, this space of time being called a "glum" (a period of gloom). In the following bit of doggerel we are hurried unceremoniously into another glum:

|

Dingle, dangle, farthing candle, Put you in the stinking dog's hole. For thirty-one speak or look off for sixty-two. |

Anyone who happened to look off her work or to speak during the glum from thirty-one to sixty-two received the imposition of another glum of thirty-one pins. The cry of relief when the work was done sometimes took the form of

|

Tip and stitch turn over, Let it be hay or clover. My glum's done! |

The great question ever in the mind of the worker was, Would she get her work done before dark? for to be obliged to work by candle-light except between Tanders [St. Andrew's Day, Nov. 30th] and Candlemas [Feb. 2nd] was the bitterest of punishments; hence the tell - one girl singing the first couplet:

|

19 miles to the Isle of Wight Shall I get there by candle light? |

and another in sing-song replying,

|

Yes, if your fingers go lissom and light, You'll get there by candle light. |

A scrap of village history sometimes wove itself into these lace tells. One is the lurid story of a girl and a worthless lover. After playing with her affections he turned from her, and resolved to murder her. In order to get her into his power he requested her to meet him on a dark night under a certain tree. He and an accomplice arrived there before the appointed time, and at once set to work to dig the grave, being lighted by a lantern, which they tied to the tree, and the ghastly streaks of blue summer lightning. The girl approached the spot earlier than she was expected, and seeing from a point of vantage two men instead of one, her suspicions were aroused. The murkiness of the night added to her fears. At the same moment "the Fox", as she called her faithless lover, happened to catch sight of her, and imagining that she was not alone, he gave the alarm to his companion, and they made off. She arrived home in safety, and she tells her tale in a couple of stanzas...

| The Fox |

|---|

|

19 miles as I sat high Looking for one, and two passed by, I saw them that never saw me - I saw a lantern tied to a tree. The boughs did bend, and the leaves did shake I saw the hole the Fox did make. The Fox did look, the Fox did see I saw the hole to buy me. |

...

The following tell also reveals the Bucks lace-maker towards the gruesome, the uncanny and the truculent.

| The Fox |

|---|

|

Get to the field by one Gather the rod by two Tie it up by three, Send it home by four Make her work hard at five Give her her supper at six Send to her bed at seven Cover her up at eight Throw her down stairs at nine Break her neck at ten Get to the well-lid by eleven Stamp her in at twelve. How can I make the clock strike one, Unless you tell me how many you've done? |

In the last two lines allusion is made to the plan sometimes followed in the lace schools, and already in these pages alluded to, of counting the number of pins stuck and calling out at every fifty or a hundred; each girl endeavouring, in order to show her dexterity, to be the first to call out.

...

That the Bucks lace-makers, however, could appreciate the pleasant as well as the morbid, is evidenced by the following, which was sung at Weston Underwood.

|

A lad down at Olney looked over wall, And saw nineteen little golden girls playing at the ball. Golden girls, golden girls, will you be mine? You shall neither wash dishes nor wait on the swine. But sit on a cushion and sew a fine seam, Eat white bread and butter and strawberries and cream. |

The "golden girls" were, of course, the gold-headed pins that marked the footside of the lace. The word "nineteen" runs in many of the tells, that being the number at which counting often commenced.

The following, too, has nothing in it of the charnel-house.

|

Up the street and down the street With windows made of glass; Call at Mary Muskett's door - There's a pretty las! With a posy in her bosom, And a dimple in her chin; Come, all you lads and lasses, And let this fair maid in. |

(The name of any girl could be inserted.)

Then there was "Round the Pot of Lavender, John" and "The Ravens", and a tell that recorded "The Woes of Arabella", who died of a broken heart; but of none of them have I been able to obtain the words. All these belong to North Bucks. Enquiry in the south of the county has elicited the reply that nothing was there sung at the pillow except the monotonous

| Nineteen miles have I to go. |

The Bedfordshire Tells are of an entirely different character from those of Buckinghamshire. They turned less on bones, gibbets, and horrors customarily referred to under one's breath, than on the neatness of the village lace-maker's appearance, the wisdom of choosing one of those comely "Bedfordshire girls "to be your sweet wife", and the anticipated joys of the approaching wedding; moreover they are enlightened with an occasional gleam of pawky humour. The following evidently dates from the 18th century:

| The Bedfordshire Farmer |

|---|

|

In Bedfordshire lived a rich farmer, we hear; A Bedfordshire maiden had lived there a year. She started for home on a short holiday, When a highwayman stopped her upon the highway. She screamed out with fright, she screamed out with fear, But help ('twas the Bedfordshire farmer) was near. The highwayman, hit by a blunderbuss, died: And there soon was a wedding, and she was the bride. |

No doubt more than one Bedfordshire maiden subsequently took a stroll on the highway on the off-chance of being stopped by a "gentleman of the road". But there is another version of the story, according to which, the girl not only screamed out, but stunned the highwayman with a serviceable stick, when another highwayman appeared, and it was this second gentleman who received the attentions of the Bedfordshire farmer. The denouement, however, was the same in both cases. Let us hope that the wedded pair lived harmoniously; for that there was sad bickering in some Bedfordshire homes is from the following tell painfully evident.

| The Old Couple |

|---|

|

There was an old couple, and they were poor, They lived in a house with only one door, And poor old folk were they. And the poor old man said he wouldn't stay at home, And the poor old woman said she wouldn't sleep alone, And poor old folk were they. And she said, "If you've any love for me, You'd fetch me an apple from yonder tree." And poor old folk were they. He fetched her a apple and laid it on the shelf, And said "If you want any more, you can fetch them yourself!" And poor old folk were they. |

To judge by the next tell, it was the custom of Bedfordshire young women, when a man offended them, to throw a turnip at him:

|

Nineteen miles to Charing Cross. To see a Black Man ride on a white horse. The rogue was so saucy he wouldn't come down, To show me the road to the nearest town. I picked up a 'turmut' and cracked his old crown, And make him cry 'turmuts' all over the town. |

On the whole, we are inclined to sympathise with the "Black Man", whose punishment seems to have been out of all proportion to his offence. Who was he? Evidently, Mr. E. Godfry the lace-buyer, with whom the lace-makers sometimes had differences; and a lampoon in the shape of a lace tell was their revenge. Another rhyme of the neighbourhood refers to the same person and to a lady buyer.

|

Behind in this meadow you'll find a dry land, Two beauties of Bedford, and there do they stand; He on the white horse and she on the grey, And so these two beauties go riding away. |

The word "beauties" is evidently intended as sarcasm.

At Ickwell Green, near Northill, used to be sung an amusing song called "Hodge of the Mill and Buxom Nell", which describes how Hodge, who was given to flirtation, surrendered at discretion to the lady on learning that she was worth as much as "fifty shillings". "No Wife like a Lace-maker" comes from Wootton, "The Roving Blade" from Bromham, "The Deserted Lover" from Ravensden, and "Amen, said the Fool," a sarcastic rhyme about various village characters, nobody from the parson to the blacksmith being perfect, was sung in many Bedfordshire lace schools some fifty or sixty years ago.

The following was used by children in the lace schools of Renhold.

|

Needle pin, needle pin, stitch upon stitch. Work the old lady out of the ditch. If she is not out as soon as I, A rap on the knuckle shall come by and by. A horse to carry my lady about - Must not look off till 20 pins be out. |

They then counted twenty pins, and if anyone looked off before she had got through th twenty, the others would call out:

|

Hang her up for half an hour, Cut her down just like a flower. |

The girl referred to would then put in another pin and reply:

|

I won't be hung for half an hour, I won't be cut down like a flower. |

And who can blame her?

The Northants Tells have none of the gruesome features that characterises those of Buckinghamshire, and they are less hoydenish and more sentimental than those of Bedfordshire. The Northamptonshire maidens do not gloat over ghosts, corpses, black coffins and gibbets, nor do they throw turnips at the heads of inoffensive gentlemen who happen to be passing on horseback. They had no taste for dark parables. In the Northants tells, while admission is made of the hardship of existence, the future is looked forward to not without hope.

|

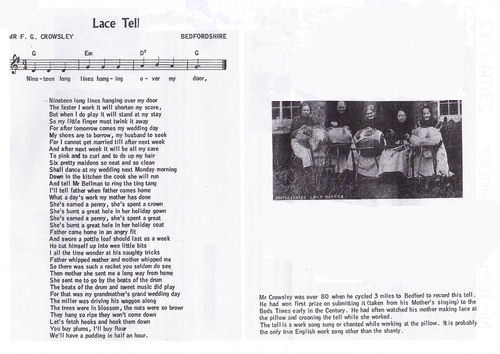

Nineteen long lines hanging over my door, The faster I work it will shorten my score, But when I do play it will stand at my stay So my little finger must twink it away For after tomorrow comes my wedding day My shoes are to borrow, my husband to seek For I cannot get married till after next week And after next week it will be all my care To pink and to curl and to do up my hair Six pretty maidens so neat and so clean Shall dance at my wedding next Monday morning Down in the kitchen the cook she will run And tell Mr Bellman to ring the ting tang |

There are twenty two more lines.

The Northants girls were indeed more optimistic than their sisters in High Bucks and West Beds. They seemed to grasp that life consists not of hours as indicated by the clock but of the hours in which one is cheerful. They had dropped into the habit of hanging bright pictures in their minds.

Another tell runs on "the cherry trees in blossom", the brown nuts that "hang so ripe", (for in the lace world of Northants cherries blossom and nuts ripen in the same month); and the preparation for a plum pudding which would take less than half an hour. Then there is the "Song of the Nutting Tree", which begins:

|

I had a little nutting tree, And nothing would it bear, But little nutmegs For Galligolden fair. |

But who Galligolden was, and what she wanted the silver nutmegs for, is not clear.

At Yardley Hastings they sang:

|

Twenty pins have I to do; Let ways be ever so dirty. Never a penny in my purse, But farthings five and thirty. Betsy Bays and Polly Mays, They are two bonny lasses; They built a bower upon the tower, And covered it with rushes. |

I give this jingle as it was told me. It evidently refers to the old custom of carrying rushes and garlands to church on Rush-bearing Day - a custom that is still observed in the North of England. "Upon the tower" should probably be "within the tower". Of course any names could be substituted for Betsy and Polly.

The song of "Long Lanken", which, with its trimmings of corpse and gallows, might seem damaging to the theory of the Northants tells, is not really a Northants song at all, having been imported from the Scottish border.

The tells of all three counties - Bucks, Beds and Northants - are influenced by the superstition of the people; nor is this surprising, seeing that in every town and village there is some story of a supernatural character - of ghosts that stalk and gibber and wizards that peep and mutter. The Devil and Headless Horseman traditions of Olney, and the names "Great Goblin's Hole" and "Little Goblin's Hole", of Turvey, would alone bear witness to the insatiable appetite of the lace-makers for the uncommon and the uncanny.

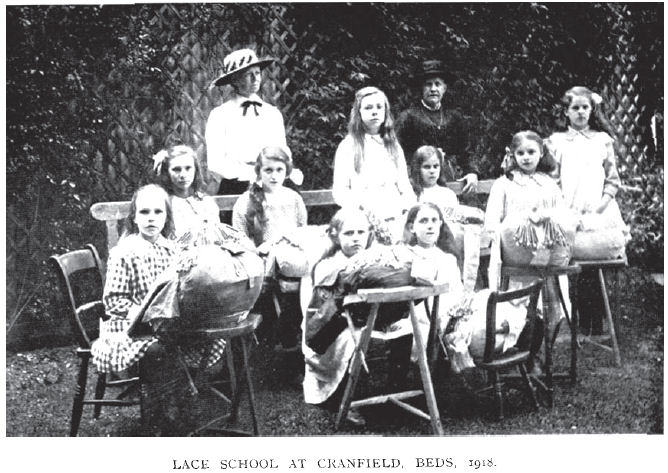

We are told that the effect of thirty or forty children's voices uniting in the sing-song of these tells would never be forgotten by anyone listening to them for the first time, and that the children found the singing of the tells a real aid to them in their work. It was a very pretty sight in a lace school of some 30 children, some of them little more than babes, to see, as an old lace-maker put it, "all the fingers and all the bobbins going". Singing at the pillow, too, was particularly helpful both to adults and children in dull weather - which, as an old Newport Pagnell lace-maker said, used to "mommer" her (make her feel stupid) and make her feel as if she had no "docity" in her (pronounced "dossity". The word really means "aptness to learn".)

The account above is from about a hundred years ago, and very much of its time. I do not think that today we would approve of children "some of them little more than babes" being expected to work! I have also not repeated one lace tell which is vile. The casual references to beatings are bad enough.

Thomas Wright did not seem to recognise that two of the tells above are merely variants of well-known nursery rhymes, "Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross" and "I had a little nut tree and nothing would it bear". "Long Lanken" is a well-known folk-song, as were some of the others, presumably. It is a shame that we have lost "No Wife like a Lace-maker"!

There are various references to money in these tells.

"Fifty shillings" - there were twenty shillings to the pound, so this was £2.50

"Farthings five and thirty" - four farthings to the (old) penny, and 240 old pennies to the pound, so this was under 4 (new) pence.

"Penny" - an old penny - there were 240 of these to the pound, so less than half a (new) penny.

"Crown" - five shillings, or a quarter of a pound (now 25p).

"groat" - four (old) pennies, so less than two (new) pennies.

Click here for more about old English money.

There is a reference above to the tell "Nineteen long lines hanging over my door". Thomas Wright only gives the first part. Here is a more complete version:

|

Nineteen long lines hanging over my door, The faster I work it will shorten my score, But when I do play it will stand at my stay So my little finger must twink it away For after tomorrow comes my wedding day My shoes are to borrow, my husband to seek For I cannot get married till after next week And after next week it will be all my care To pink and to curl and to do up my hair Six pretty maidens so neat and so clean Shall dance at my wedding next Monday morning Down in the kitchen the cook she will run And tell Mr Bellman to ring the ting tang I'll tell father when father comes home What a day's work my mother has done She's earned a penny, she's spent a crown She's burnt a great hole in her holiday gown She's earned a penny, she's spent a groat She's burnt a great hole in her holiday coat Father came home in an angry fit And swore a pottle loaf should last us a week He cut himself up into wee little bits I all the time wonder at his naughty tricks Father whipped mother and mother whipped me So there was such a racket you seldom do see Then mother she sent me a long way from home She sent me to go by the beats of the drum The beats of the drum and sweet music did play For that was my grandmother's grand wedding day The miller was driving his waggon along The trees were in blossom, the nuts were so brown, They hang so ripe, they won't come down Let's fetch hooks and hook them down You buy plums, I'll buy flour We'll have a pudding in half an hour. |

Oddly enough, Thomas Wright quotes bits of the second half, but seems to think they belong to a different tell.

© Jo Edkins 2017 - return to lace index